The greatest downside of nationalism (for the nationalist at least) is that despite all your eloquence on unity and common purpose, your nation doesn't always get along too well. In fact, when coupled with profound economic upheaval, conflict often emerges. The first Industrial Revolution saw a revolution in the means of production that took some time to adjust to. Along with the political turmoil of the period, it provoked revolutions in 1830 and 1848. However, the second Industrial Revolution saw no such thing. I posit two principal causes:

1. The Second IR was not as 'revolutionary' as the first. As the textbook mentions, the Second IR was principally an "increas[e] in the scope and scale of industry", not a transformation of industry or the creation of industry. This made it less of a shock to people.

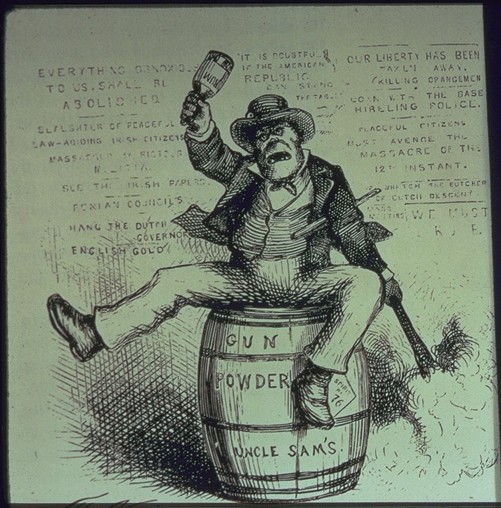

2. Rather than take up arms, reformers principally felt their calling lay in the political process. The development of states based around nations meant a greater connection between the state and its people (in part because of democratization, in part because the legitimacy of the state was now fundamentally in its people, not the royal line or aristocracy [Russia withstanding]). In places with developed political institutions, like Britain, violence was at a minimum, whereas in France events like the Paris Commune led to violent crackdowns.

Change therefore came in the form of Socialist parties and workers movements that sought to work within the context of a 'bourgeois' government to improve the lot of the working class. Socialist thinkers like Eduard Bernstein moderated Marx's vision and used the vehicle of social institutions to achieve change rather than syndicalists and anarchists. A useful analogy, perhaps, is the AFL vs. the Knights of Labor from US history. 'Mass politics', as the textbook calls it, organized huge voting blocs within the political apparatus and were thus taken more seriously by the established states of the day.

Finally, this period of the "Gilded Age" is often cited by critics of capitalism for being an era of cartelization and monopolization. However, as the textbook correctly mentions, FREE TRADE proved to be one of the best deterrents to cartel behavior in countries like Britain (top right pp. pg. 829). FREE TRADE (i.e. foreign competition for the cartel, which makes it more difficult to sustain prices above the market rate) can defeat monopolies and cartels far better than regulation.